“I only think about what I can see with my eyes, I’ve never seen any angels” says Gustave Courbet. “I only believe what I cannot see but what I feel” says Gustave Moreau. This is the main difference between Realism and Symbolism, between the decision to place the objective world as the main focus of its investigation and the choice of penetrating and going beyond appearances. A universe which is measurable in opposition to a world that is in relation to all that which is transcendent, poetic, visionary, religious. The symbol becomes the revealing element of the secret essence, suggesting mysterious and cryptic meanings, hence a vehicle to make forces that have fallen into the depths of the unconscious human existence perceptible again. “Naming an object is like suppressing poetry, which consists of the happiness of guessing little by little” said Mallarmé, a symbolist poet. The artists express themselves through metaphors that force the user to perform an intuitive search for contents in order to arrive at solutions that are not immediately decodable.

The movement had different facets and involved not only the visual arts but also literature and music, typical of the last two decades of the nineteenth century. The artists were influenced by the philosophical ideas of the second half of the century, from Schopenhauer to Nietzsche but also from Bergson.

The latter said that: “The perception of the essence requires an enlightened attitude”, as he was convinced that reality could only be achieved using intuition, as this faculty has a cognitive value, aiming for an instant understanding of things and not mediated by logic. The cause for which we assist to an emerging European aspiration to investigate the secret meaning of things is born from fatigue against the domain of scientific knowledge, progress, positivism and nostalgia for the loss of core values. The positivist spirit that had dominated the French and European culture admits only the reality of nature while the symbolist spirit believes in a universe based on religion, aesthetic contemplation, artistic creation. A new pictorial language that was called “idealist, synthesist, symbolist, subjective and decorative” was born. Symbolism is not a movement but a real taste of the great current which expresses a profound existential malaise.

One of the major themes of Symbolist is in fact decadence, a term used to define the end of the century. The protagonist of the decadence is the dandy, the prince of an imaginary reality, a symbolist figure for excellence as researcher and explorer of the deep beauties of the soul, aided by modern psychology, which denied that the man was the master of his own self. Beauty as a weapon against tedium of life was thus one of the favourite themes of the great French author Baudelaire in “The Flowers of Evil”, the most famous collection of poems of the nineteenth century.

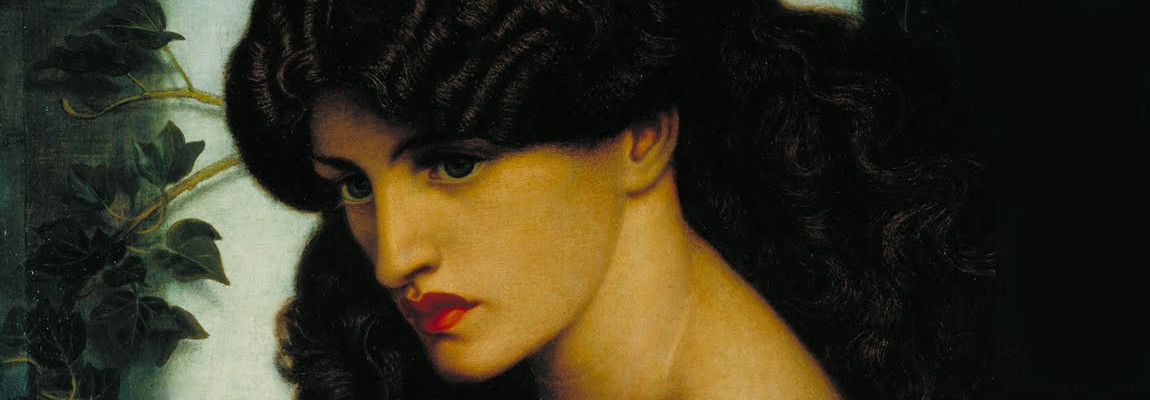

The topics of Symbolism, in brief, are mystery, dreams, nightmares, secrets, the psyche, religious syncretism, in which myth and ancient Eastern rites are combined, and eros, understood both as the duplicity of love and death. The painter developed a new interpretation of the female image in which the eternality of the feminine figure concentrates in itself the mystical power of creation and fertility on the one hand, and temptation on the other. A woman without mercy, also known as vampire-woman, is expressed in the figure of Salomè, who uses her beauty and charm to win over the man, by using her power of charm to destroy him. Goya with his series of Caprices can be considered a precursor of Symbolism. These etchings made between 1797 and 1798, have one of them depicting “The Sleep of Reason Produces Monsters”, representing a man who sleeps and dreams as a crowd of ghostly shadows, his nightmares, pounce against him to tell him how imagination, when abandoned by reason, produces inconceivable monsters.And it is precisely to this form of imagination, that can open up dangerous dimensions, that Symbolism subdues enthusiastically.

Friedrich, further precursor and extraordinary exponent of German Romanticism, states that: “The painter should not just paint what he sees but also what he sees within himself”.